8th November 2022

What is the difference if someone says ‘I have lived here for five years’ or ‘I have been living here for five years’? If you are reading a newspaper article and the writer states ‘an agreement has been reached’ rather than ‘an agreement was reached’, why did they make this choice? Why do we sometimes use the present tense to talk about the future (‘I fly there on Tuesday’)? Or the past (‘I go to the park and see this big dog and it’s chasing this man’)?

All languages have methods to differentiate periods of time. Some, such as Chinese, do this through context and using various time phrases. In English, tenses are important to convey which period of time we are talking about. Therefore, it is unsurprising that there are dedicated units on tenses on the Trinity CertTESOL course, as tenses are central to language learning syllabuses in both English for general and specific purposes. However, as hinted at above, the tense system in English is complex and can be confusing for both students and teachers. In the first part of this blog, I will clarify the basics of English tenses and aspects. In the second part, I will explore some common difficulties learners face and methods to helping them overcome problems as well as general ideas for the teaching of tenses.

Background: let’s deal with the basics:

What is a tense? How is that different from an aspect? How many tenses and aspects are there in English?

The technical definition of a tense is a change in verb form to denote a change in the time being referred to. According to this definition, there are only two tenses in English: the present (I eat) and the past (I ate). Reference to the future is achieved not through changing the verb form but through other means such as adding the modal verb will (I will eat).

As for aspects, a simple definition would be that it expresses an event’s nature (temporary, ongoing, relationship to other events, etc. - more on this later). Depending on your point of view, there are between 2 and 4 aspects in English: the simple (I eat), the continuous (I am eating), the perfect (I have eaten) and the perfect continuous (I have been eating). The reason for the disagreement is that some would see the simple as the absence of an aspect and the perfect continuous not as a separate aspect, but the combination of the perfect and continuous aspects.

You will notice that, without even getting into the differences between different tenses and aspects, things are already getting a little confusing. From a teaching perspective, these distinctions are not always particularly important or helpful. This is, perhaps, why course books refer to ‘the present continuous tense’ or ‘the past perfect tense’. It is tempting to refer to the perfect tense, as Michael Swan argues, ‘for the sake of simplicity’. However, I do feel that the distinction is important. Because tense refers to time, if we talk about the ‘the present perfect tense’ and ‘the present perfect continuous tense’, we may reasonably expect them to denote some difference in the time period being talked about. However, if we say ‘I have lived in Dublin for one year’ or ‘I have been living in Dublin for one year’, the time period we are referring to is exactly the same. The possible difference is the temporariness of this event (this example is discussed further later in this blog). So, I think it is useful from a teaching perspective to talk about the present perfect rather than the present perfect tense.

Examples of each tense

The next step is to differentiate the 12 basic tense/aspect combinations in English. Below, I will give an example of each which is true for me at the time of writing with a brief explanation of the function of each example. For teachers who are just starting to get to grips with these different tenses and aspects, I suggest writing something similar yourself; it helped me greatly when I was starting out.

Past:

Past simple:

I went to Sanya last month.

(completed action at a specified time in the past)

Past perfect:

When I got back to Shanghai, some of my friends had left.

(positioning one past event after another)

Past continuous:

I was sitting on the beach this time two weeks ago.

(action in progress at a particular time in the past)

Past perfect continuous:

I had been baking bread regularly before I went away.

(positioning a past repeated action before another particular point in the past)

Present:

Present simple:

I live in Shanghai.

(statement of fact)

Present continuous:

I am reading ‘What I talk about when I talk about running’ by Haruki Murakami.

(repeated action started in the past and continuing to the present)

Present perfect:

I have visited several countries in Asia.

(experience in my life up until now)

Present perfect continuous:

I have been going to the gym regularly for over a year.

(repeated action started at a specified time in the past and continuing up to the present)

Future:

Future simple:

This time next year, I will be in another city.

(future fact)

Future continuous:

This time next month, I will be packing my belongings.

(action in progress at a specified time in the future)

Future perfect:

By October, I will have left Shanghai.

(Action completed by a particular time in the future)

Future perfect continuous:

This time next year, I will have been working in education for over 13 years.

(continuous action continuing for a specified period of time at a certain time in the future.

General differences between aspects

As mentioned above, aspects characterise an event in some way. There are some general tendencies about the way they do this. Drawing on Martin Parrot’s Grammar for English Language Teachers, I will now outline some of these tendencies (I use the term tendencies rather than rules very deliberately here and none of these can be seen as hard and fast rules) below.

Simple:

The simple is generally used to describe facts (‘I live in Shanghai’, ‘I lived in Cambridge before’, ‘the birds will come back next summer’), habits (‘I played football twice a week when I was young’, ‘I go to the gym every Monday’) and to show spontaneity or some change in a situation (‘I’ll come too!’, ‘I now pronounce you man and wife’).

Perfect:

The perfect is generally used to connect events that happened at one time to another time (‘When I got back to Shanghai, my friends had already left’: connecting one past event to another past event, ‘I have visited many countries in Asia’: connecting past events to the present to talk about experience, ‘by October, I will have left Shanghai’: showing that a future action will be completed by a particular time in the future).

Continuous:

The continuous can be used to denote temporariness (If you hear ‘I have been living in Dublin for one year’, you may expect the next sentence to be ‘but I’m moving to Cork soon’ if you hear ‘I have lived in Dublin for one year’, you may expect to hear ‘and I’ve just extended the lease on my house’ - this point though is very much a tendency and not a rule), events or actions which are in progress/unfinished (‘he’s been fixing that all morning’, ‘we’re enjoying our holiday’). The continuous is also common when talking about actions (‘I’ve been running recently’ not ‘I’ve run recently’).

Tenses then (including the future ‘tense’), convey which time period a speaker or writer is referring to, while aspects give more information about the nature of an event.

Let's put this into practice

So far, I’ve differentiated tense and aspect, given some examples of the twelve main tense/aspect combinations in English and looked at some patterns regarding how different aspects are used to express different meanings. Next, I will outline some ways in which we can convey these meaning effectively to students. I will describe a three step model for the teaching of tenses, outline three key issues in the teaching and learning of tenses - namely confusion over contextualised meaning, a focus on fluency to the detriment of accuracy and a lack of concord between time and tense - and, finally, look at example issues that learners may face in these three areas and how we can help them with those.

A model for the teaching of tenses

On initial training certificate courses such as the Trinity College CertTESOL & Cambridge CELTA, trainees are often taught, when presenting grammar, to follow the stages: meaning, form and pronunciation and given one of the many acronyms used on such courses to remember it: MFP. An example of this model in use to teach the future perfect is given below:

Meaning:

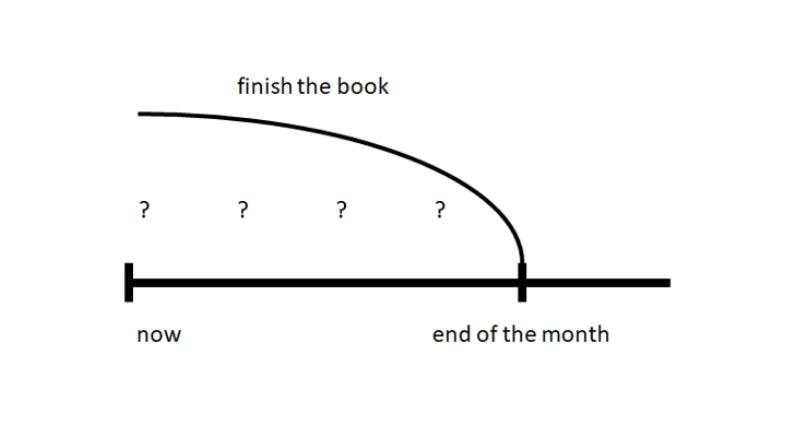

The teacher tells the students that she is reading a book about ancient Greece and it’s taking a long time, but ‘by the end of the month, I will have finished the book’. She draws the following timeline on the board:

She explains that she’s not sure exactly when she’ll finish but it will definitely be by the end of the month. She then asks the following concept checking questions: ‘have I finished the book?’, ‘might I finish it tomorrow?’, ‘next week?’, ‘next month?’

Form:

The teacher separates the example sentence into parts as below:

by / the end of the month / I / will have / finished / the book

She then draws a substitution table and elicits what other words or phrases can replace each constituent part of the sentence as below:

| by | the end of the month | I | will have | finished | the book |

| by | the time her husband comes home | she | will have | had | her dinner |

| by | Tuesday | he | will have | run | 5 km |

| by | next year | we | will have | graduated |

Pronunciation:

The teacher models two ways of pronouncing part of the sentence:

1) I will have (/aɪ wɪl hæv/) finished the book.

2) I’ll have (/aɪl əv/) finished the book.

She asks students which sounds more natural. She then explains and models again the second example (contraction of ‘will’, elision of /h/ and weak form of the vowel in ‘have’ (google ‘connected speech in English’ for more details)). She then shows how a similar process occurs when other pronouns (he, she, etc.) are used.

What I have described above is a fairly standard grammar presentation you may expect to see on a CertTESOL or CELTA course. This model makes sense in that, for students to be able to use a particular grammar point in their spoken language, they need to know what meaning they are expressing, how to form the sentence correctly and how to pronounce it naturally. This is just one example and there are, of course, many different ways to achieve each stage of the model. I don’t want to go into this too deeply here but would like to make a few points:

- This example could be described as quite ‘teacher-centred’. A more student-centred way of analysing this structure might be to have the students find examples from a text, to have them work out the meaning and form from those examples and to have them identify the pronunciation from an audio file. While there are great benefits to a student-centred approach, I do feel that, as language teachers, we should be able to present an aspect of grammar as there are many teaching contexts around the world where students may be resistant to a student-centred approach and the ability to explain a grammar point without pre-prepared materials such as texts is something we should all have. I would suggest mastering the teacher-led approach outlined above before trying to move onto the more student-centred approaches.

- The example doesn’t include any metalanguage: the teacher at no point mentioned ‘the future perfect’ or that ‘finished’, in this case, is the ‘past participle’. Personally, I try to avoid the use of metalanguage in grammar teaching as I think it adds another layer of difficulty and there may be students in the room who don’t know what a ‘past participle’ is. However, there may be teaching contexts where use of metalanguage is appropriate, such as on a course where a focus on more theoretical aspects of grammar is part of the learning outcome (I’m thinking about state school examinations in some contexts).

- A strong focus on form may be unnecessary. For example, if students are learning the present continuous to talk about the future (‘I’m seeing them tonight’), we can reasonably assume that they are familiar with this structure to talk about the present. A quick check that they know the form may be all that is necessary.

Issues with contextualised meaning

Connected to this final point, in almost all of the grammar lessons I have observed, even at Diploma level, teachers seem to focus more heavily on form than meaning. Furthermore, the focus on meaning (as in the example above) is often focused solely on time-related meaning. As mentioned above, different aspects express meanings which are not time-related such as temporariness, Furthermore, the same tense/aspect combinations can be used to express different meanings in different contexts (I will use the term ‘contextualised meaning’ going forward). If someone says ‘by the end of the month, I’ll have finished the book’, they are expressing something quite different (a kind of promise/resolution) compared to if they say ‘by the end of August, I’ll have finished my dissertation’ (looking forward to the end of a long and difficult task). Context also plays a role in a speaker or writer’s choice of tense and aspect. Clearly, then, when teaching tenses and aspects, a focus on the time period alone is insufficient. We need to make learners aware of the different functions that tense/aspect combinations express.

I am in agreement with Laura Collins, who argues that, while form can be an issue for beginner learners, the greater problem in the long term comes from meaning. While it may be common to hear errors such as ‘I have ate’, these tend to be quite easily corrected and less persistent than ones where students select the wrong tense/aspect combination to express a particular meaning or avoid using more complex constructions altogether. Consider the following learner error from a 2007 study by Collins:

(he) rode his bike 10 kilometres. … After that, the weather was nice so my mother was swimming in the ocean and my father was riding his bicycle.

In her commentary, Collins points out that, while the student was able to form the past simple and the past continuous, she was not able to differentiate when one is preferred to another. If one of your students made this error how would you go about correcting it? And which would you feel more confident in correcting, this one or the previously mentioned ‘I have ate’?

Explaining the relationship between contextualised meaning and tense and aspect can be as challenging for teachers as understanding and applying it is for students. Fortunately, most good grammar books, including the two mentioned in the reference section of this blog, can offer a good starting point for our own understanding and, therefore, our explanations for students. There are also some more practical examples of how this kind of meaning can be taught later in this blog. One final point I would like to make before moving on is that we can help ourselves in our lesson planning if we make the focus meaning rather than form from the beginning. Rather than ‘I’m teaching a lesson on the present perfect’, think ‘I’m teaching a lesson on talking about experience’ (also, if students ask you the topic of your lesson, the latter will invariably get a better reception than the former!).

Focus on fluency over accuracy

While there is a strong link between form and meaning, there are times when learners may make errors in form because they are trying to communicate meaning in the most efficient way possible and this is often by transferring ways of marking time and other meaning from their first language.

There are times when this will, of course, cause misunderstanding on the part of the listener but others where it may not. There are certain grammatical features of a language which do not affect the meaning being conveyed. However, when errors occur in these areas, they can grate on the ears of people who speak those languages as their first language. Perhaps the most classic example of this is when learners of French select the wrong form of the definite article (le or la) for the gender of a noun (for example, apples are feminine in French so ‘the apple’ is ‘la pomme’, while milk is masculine so ‘the milk’ is ‘le lait’). Examples in English are use of the wrong preposition (e.g. I’m going there for buy some fruit) and forgetting the third person ‘s’ in the present simple (e.g. she like running). Although tenses and aspects are extremely important in conveying meaning in English, when learners employ other methods of conveying the same meaning, an error in tense or aspect will not necessarily lead to misunderstanding on the part of the listener and the learner may, therefore, not place great importance on using the appropriate tense/aspect combination. One example of such an instance is explored in more detail below.

Lack of concord between time and tense

There are many examples in English where the tense being used does not match with the time being talked about. This is especially true when talking about the future since, as mentioned in the first part of this blog, there is technically no future tense in English. It is also the case in other instances, though, such as the use of present tense constructions to tell an anecdote (‘I go to the park and I see this big dog and it’s chasing this man…’).

Common learner errors and teaching ideas

I will now move on to outline three of the most common learner errors with tenses and aspects which I have experienced during my time teaching and training that I feel illustrate the three problem areas outlined above. These are:

- Confusion between the past simple and present perfect (caused by confusion over contextualised meaning).

- Avoidance of the use of tense and aspect (caused by a focus on fluency over accuracy leading to transfer from students’ first language).

- Over-use of ‘will’ to talk about the future (caused by a lack of concord between time and tense in English).

I will also give some examples of how I have dealt with such errors in the past. This list is supposed to be illustrative rather than exhaustive and will undoubtedly have been affected by the particular teaching contexts in which I have worked. You will likely need to do more research into the particular issues your learners face and I would suggest Learner English, edited by Michael Swan and Bernard Smith as a good starting point for this. I hope from this list, though, you can get an idea of how students may struggle with tenses and aspects and why they make such errors.

Confusion between the past simple and present perfect

The decision of when to use the present perfect or the past simple can cause issues for students. This is likely because both are used to talk about events which occurred during the same time period (in the past). It is common to hear errors like:

‘The visitor is in the waiting room. I have opened the door for him.’

‘I have been to the gym yesterday.’

The past simple would be more appropriate in the first example because the event has a definite end point and is fully completed. In the second, it would be more appropriate because ‘yesterday’ is a fully completed period of time. Notice that if the contextualised meaning is changed slightly, these two utterances could be correct:

The visitor is parking his car. I have opened the door for him.

(The door was opened at the same time but because the visitor needed to park his car he didn’t immediately walk through it, thus the full event has not yet been completed.)

I have been to the gym once this week.

(She still went to the gym yesterday but is emphasising the number of visits in an unfinished period of time i.e. this week.) Note: this use of the present perfect is common in British English, but the past simple would be preferred in American English.

Therefore, these errors quite possibly occur because learners are failing to recognise how contextualised meaning affects the choice of tense and aspect when talking about an event which occurred in the past.

Teaching ideas:

Where there are two forms which learners are confused between, a lesson which differentiates the two can be useful. One way in which I have done this with regards to the past simple and present perfect is outlined below:

- The teacher asks students what they think he has done in the last year or so. They discuss in pairs.

- The teacher then tells students about some of his recent activities, using sentences like ‘I went to Japan in January’ and ‘I’ve been on two trips this year’.

- The teacher hands out a list of sentences with the time phrase missing, repeats the talk and students fill in the missing time phrases.

- The students discuss why some sentences use the past simple and others use the present perfect based on the time phrase.

- The teacher takes feedback and checks that students understand that the present perfect is used to talk about unfinished periods of time and the past simple for finished ones. He checks that students are clear on the form of both structures and points out the contractions (I’ve, she’s, etc.).

- Students are put into groups and asked to make sentences using stems such as ‘some of us…’, ‘all of us…’, ‘one of us…’ and both forms (e.g. ‘all of us have drunk coffee this afternoon’, ‘one of us went shopping yesterday’).

- Students are paired up and talk about their recent activities in a similar way to which the teacher did at the start of the lesson.

This lesson follows a similar structure to many traditional grammar classes: a warmer, model of the grammatical structures being studied, analysis of meaning, form and pronunciation, a controlled practice activity and a free practice activity. Where it differs is that the main focus of the lesson is on contextualised meaning rather than form or basic time-based meaning.

Avoidance of the use of tense and aspect

Some students tend to use the present simple as a default regardless of the time they are talking about and the meaning they are trying to express, for example ‘I go swimming last night’, ‘I finish my studies by next year’. Notice that both of these examples contain an adverbial of time (last night, by next year). There is a strong possibility that the learners in question are affected by their first language in these cases as this is how time is differentiated in Chinese. With some Chinese students, I have particularly found this with the past tense. Once they have marked the time in some way, they may revert to present simple. Aside from the errors noted above, it is also common to hear something like:

‘I went to the supermarket and I buy some groceries, then I go home.’

There is a possibility that the learners feel they are conveying the time period they are talking about using adverbials or an initial use of the past tense and, therefore, there is no need to concern themselves with the tenses and aspects they are using after that. Certain students are certainly more interested in speaking fluently and being understood than with grammatical accuracy. If you have ever found yourself saying ‘no matter how many times I correct that error, they just keep on making it’, chances are that your students’ language use is being affected by this attitude towards grammatical accuracy.

It may be, therefore, that an avoidance of using certain tenses is caused by students focusing on fluency over accuracy and this could be exacerbated by them relying on more familiar ways of marking time from their first language.

Teaching ideas:

First, it is important to note that there is a school of thought which says that, if learners can be understood by transferring the rules of their first language into English and using those to get their meaning across, there is no need to correct this regardless of how it sounds to first language English speakers. Where English is a tool for international communication, the impression of an Australian or a Canadian regarding a Chinese speaker’s use of tenses is less important than whether a Japanese colleague can understand their meaning. There are, of course, other scenarios where ‘poor grammar’, as an enrolment officer or hiring manager might see it, could cost a student a place at university or a job.

As far as I see it, there are two important points to be born in mind:

- Is the student aware that they are making the error and of the possible negative consequences of this?

- Is meaning affected?

On the first point, we can’t make any assumptions. It may be that the learner is so caught up in expressing the meaning they want to get across that they are not fully aware that they are making an error in tense. It may be that quietly saying ‘past tense’ while they talk to their partner is enough to get them back onto the right track. Where we see a pattern of the same error occurring many times, though, it may be a case that learners are aware but don’t place a great importance on grammatical accuracy. We then have to turn to the issue of whether they are aware of the issues at hand and made a decision, based on these, not to use the past tense.

I think we can assume that most students have not read up on the idea of ‘English as a Lingua Franca’ and decided that they are using English for international communication, so they will not conform to a standard English variety but use the syntax of their own language, although, of course, some might have. In fact, it may be that, where they have learnt a formalised, grammatically focused syllabus in state school, they associate a focus on grammatical accuracy with that education system rather than communicative English. I have heard variations of the sentiment ‘native speakers don’t care about grammar’ from my own students several times. While this may be true in some circumstances, as noted above, there may be instances where a lack of grammatical accuracy could negatively affect students. What is important, then, is making them aware of pertinent issues and allowing them to make an informed decision as to whether they wish to prioritise grammatical accuracy or not.

One way in which I have done this previously is through activities which help students to, as Scott Thornbury refers to it, ‘notice the gap’ between their own language use and that of a more proficient English speaker followed by a discussion on whether those differences are important. For example:

- Students discuss what they did over their winter holiday. The teacher monitors and writes down errors students make with the past tense.

- The teacher plays an audio file of himself talking about his winter holiday and students answer some gist questions.

- The teacher hands out an audio script and asks the students to underline uses of the past tense. The teacher writes students’ errors with the past tense on the board.

- The teacher asks students to discuss the differences, why they think they did not use the past tense and whether it’s important.

- The teacher takes students’ opinions and mentions some reasons they may decide not to focus on accurate use of the past tense and some issues they may have if they do not use it accurately.

With a lesson like this, students will be clear that they are making errors with their use of the past tense and can make a reasoned decision as to whether to prioritise accurate use of this tense.

There are also times, when I feel that, even when the time period is marked, failure to use the past tense can affect meaning. Take this example: What do you do just now?

It is not clear if the student is asking what someone is doing now or was doing a moment ago. These examples are clearly important to point out and correct. But, again, it is perhaps more important to point out the difficulty this causes in terms of meaning than simply the error in form.

Over-reliance on ‘will’ to talk about the future

There are a range of structures to choose from when talking about the future. While ‘will + verb’ is the most commonly used, other choices are more appropriate in certain contexts. However, many learners seem to use ‘will + verb’ when another choice would be more suitable, for example:

I will meet them at 3:00 (should be: I’m meeting them at 3:00).

The train will leave tomorrow morning (should be: the train leaves tomorrow morning).

As mentioned in the previous blog, there is technically no future tense in English. However, ‘will +verb’ is often referred to as the future simple in course books and other materials. It may be that seeing this structure as ‘the future tense’ leads students to automatically choose it when talking about the future because they are not sure which form is appropriate for the contextualised meaning they are expressing. This issue is likely exacerbated by the way in which the time and tense do not match. Namely, the present continuous and present simple are being used to talk about the future. This may seem counterintuitive to learners and they may, therefore, rely on something they are certain can be used to talk about the future.

Teaching ideas:

One way I have explained some of these differences to students is to give a simple scenario:

My friend calls me and asks me to meet him tomorrow; I say ‘OK, I’ll come’ (decision). Another friend asks my plans for tomorrow and I say ‘I’m going to meet Ben’ (plan). The next day, Ben messages me and we arrange the time and place we’re meeting. I text the second friend to invite him too and say, ‘we’re meeting at 6 at the bar’ (arrangement). The second friend wants to go there earlier and asks the bar’s opening time; I reply ‘it opens at 5’ (schedule).

Comparing and contrasting these different forms is also a good opportunity to utilise Laura Collins’ excellent suggestion that, rather than the more traditional approach of students being given a context and choosing the correct form, they are instead given a form and asked to create context. For example, students are given the utterance ‘I’ll come’ and asked to consider questions like: who said this? Who were they talking to? What had that person just said? What did they say next?

This means that students are actively thinking about meaning and how it relates to form increasing the possibility that they will be able to make appropriate choices about their choice of structure to convey the meaning they are trying to express.

When teaching tenses and aspects, it is reasonable to focus on meaning, form and pronunciation. However, a focus on form and basic time-based meaning will not be enough for learners to use tense-aspect combinations accurately. Focusing on differences in contextualised meaning, building a strong focus on this meaning into our lesson planning and understanding other reasons why learners may struggle with tense and aspect can help us, as teachers, to assist our learners in making informed decisions about how (and whether) to make the correct choice of which form to use for which context.

References:

These two books, by authors often referred to as ‘the two birds’, have been a great help to me in teaching tenses and other aspects of grammar throughout my time as a teacher.

Parrot, M. (2000). Grammar for English Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swan, M. (2005). Practical English Usage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Collins, L. (2007). L1 differences and L2 similarities: Teaching verb tenses in English. ELT Journal, 61(4), 295-303.

Swan, M. and Smith, B. (Eds.). (2001). Learner English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thornbury, S. (1997). Reformulation and reconstruction: Tasks that promote ‘noticing’. ELT Journal, 51(4), 326-335.

Ready for a TEFL course?

Take an online course adapted from the Trinity CertTESOL qualification.